SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER FOUR

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER FOUR

BILLIE HOLIDAY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

ERIC DOLPHY

July 18-24

MARVIN GAYE

July 25-31

ABBEY LINCOLN

August 1-7

RAY CHARLES

August 8-14

SADE

August 15-21

BETTY CARTER

August 22-28

CHARLIE PARKER

August 29-September 4

MICHAEL JACKSON

September 5-11

CHAKA KHAN

September 12-18

JOHN COLTRANE

September 19-25

SARAH VAUGHAN

September 26-October 2

THELONIOUS MONK

October 3-9

FOR JOHN COLTRANE

by Kofi Natambu

Coltrane subdivides the air into

massive columns of Space

He fills all the Space all the

Time with brazen mathematical emotions

Firestorms of disciplined thoughts

burn down the paths of certainty

A roaring expansion into millions of singing

labyrinths thundering toward the precise

articulation of what he knows & does not

No All the Time in all the Space

A face exploding into trillions of sounds

A heart mowing down memories

a soul sucking up the light soaking the bones

in Oceans of Energy Air charging molecules

inside holograms of Awareness

Intervals smashing stars and spitting them out

into the empty black sky

Coltrane is a terrible cleansing force

A holy dive-bomber in saxophone jets

A killer with the Healing Eye

A Melodic Arsonist

A Harmonic Hieroglyph

A Rhythmic Hurricane

Flowers that bleed

real tears (From: THE MELODY NEVER STOPS

Past Tents Press, 1991)

http://www.biography.com/people/john-coltrane-9254106

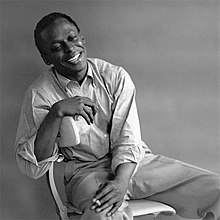

John Coltrane

Saxophonist, Songwriter (1926–1967)

Synopsis

John Coltrane was born September 23, 1926, in Hamlet, North Carolina. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, he played in nightclubs and on recordings with such musicians as Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic and Johnny Hodges. Coltrane's first recorded solo can be heard on Gillespie's "We Love to Boogie" (1951). Coltrane came to prominence when he joined Miles Davis's quintet in 1955. He died from liver cancer on July 17, 1967, in Huntington, Long Island, New York.

Early Years

A revolutionary and groundbreaking jazz saxophonist, John Coltrane was born on September 23, 1926, in Hamlet, North Carolina.

It's far from an overstatement to say that Coltrane was destined to be a musician. He was surrounded by music as a child. His father, John R. Coltrane, kept his family fed as a tailor, but had a passion for music. He played several instruments, and his interests fueled his son's love for music.

Coltrane's first exposure to jazz came through the records of Count Basie and Lester Young. By the age of 13, Coltrane had picked up the saxophone, and almost from the moment he first started playing, it was apparent he had a talent for it. The young musician loved to imitate the sounds of Charlie Parker and Johnny Hodges.

Family life took a tragic turn in 1939 when Coltrane's father, grandparents and uncle died, leaving the household to be run by his mother, Alice, who found work as a domestic servant. Financial struggles defined this period for Coltrane, and eventually his mother and few other family members moved to New Jersey in the hopes of finding a better paycheck. Coltrane remained in North Carolina, living with family friends until he graduated from high school.

In 1943, he too moved north, to Philadelphia to make a go of it as a musician. For a short time he studied music at the Granoff Studios as well as the Ornstein School of Music. But with the country in the throes of war, Coltrane was called to duty and served a year in a Navy band in Hawaii. It was during his service, in fact, that Coltrane made his first recording, with a quartet of fellow sailors.

Early Music Career

Upon his return to civilian life in the summer of 1946, Coltrane landed back in Philadelphia, where, over the next several years, he proceeded to hook up with a number of jazz bands.

One of the earliest was a group led by Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, with whom Coltrane played tenor sax. Later he hooked up with Jimmy Heath's band, where the young musician began to fully explore his experimental side.

Then in the fall of 1949 Coltrane signed on with a big band led by Dizzy Gillespie, remaining with the group for the next year and a half.

Coltrane had started to earn a name for himself. But as the 1950s took a shape, he also began to experiment with drugs, mainly heroin. His talent earned him jobs, but his addictions often ended them prematurely. In 1954, Duke Ellington brought him on to temporarily replace Johnny Hodges, but soon fired him because of his drug dependency.

Solo Career

In 1957 Davis fired Coltrane, who'd failed to give up heroin. Whether that was the exact impetus for Coltrane finally getting sober isn't certain, but the saxophonist finally did kick his drug habit. He played a six-month stint with Thelonious Monk and then embarked on a solo career.

By this period, Coltrane had created a definite sound of his own. Part of it was defined by an ability to play several notes at once, creating what would be later dubbed as his "sheets of sound."

Coltrane described it this way: "I start in the middle of a sentence and move both directions at once.”

By 1960 Coltrane had his own band, a quartet that included pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. The group, known as the John Coltrane Quartet, produced some of jazz's most enduring albums, including Giant Steps (1960) and My Favorite Things (1961).

The latter album especially catapulted Coltrane to stardom. Over the next several years Coltrane was lauded -- and, to a smaller degree, criticized -- for his sound. His albums from this period included Duke Ellington and John Coltrane (1963), Impressions (1963) and Live at Birdland (1964).

But it was 1965's A Love Supreme that may just be Coltrane's most acclaimed record. The album garnered the saxophonist two Grammy awards, for performance and jazz composition.

Final Years and Impact

In 1964 Coltrane married jazz pianist Alice McCloud, who'd go on to play in his band. Coltrane wrote and recorded a considerable amount of material over the final two years of his life. In 1966 he recorded his final two albums to be released while he was alive, Kulu Se Mama and Meditations. The album Expression was finalized just one day before his death. He died from liver cancer on July 17, 1967, in Huntington, Long Island, New York.

Coltrane's impact on the music world was considerable. He revolutionized jazz music with his experimental techniques and showed a deep reverence for sounds from other cultures, including Africa and Latin America.

In 1992 Coltrane was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. His work continues to be a part of soundtracks for movies and television, so much so that in 1999 Universal Studios named a street on the Universal lot in his honor. In 1995, the United States Postal Service recognized the late musician with a commemorative stamp. More important, Coltrane's sound has inspired generations of newer jazz musicians.

http://www.johncoltrane.com/biography.html

http://www.britannica.com/biography/John-ColtraneJohn Coltrane

JOHN COLTRANE

American musician

by The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica

Also known as

John William Coltrane

Trane

born September 23, 1926

Hamlet, North Carolina

died July 17, 1967

Huntington, New York

John Coltrane, in full John William Coltrane, byname Trane (born Sept. 23, 1926, Hamlet, N.C., U.S.—died July 17, 1967, Huntington, N.Y.), American jazz saxophonist, bandleader, and composer, an iconic figure of 20th-century jazz.

Coltrane’s first musical influence was his father, a tailor and part-time musician. John studied clarinet and alto saxophone as a youth and then moved to Philadelphia in 1943 and continued his studies at the Ornstein School of Music and the Granoff Studios. He was drafted into the navy in 1945 and played alto sax with a navy band until 1946; he switched to tenor saxophone in 1947. During the late 1940s and early ’50s, he played in nightclubs and on recordings with such musicians as Eddie (“Cleanhead”) Vinson, Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Johnny Hodges. Coltrane’s first recorded solo can be heard on Gillespie’s “We Love to Boogie” (1951).

Coltrane came to prominence when he joined Miles Davis’s quintet in 1955. His abuse of drugs and alcohol during this period led to unreliability, and Davis fired him in early 1957. He embarked on a six-month stint with Thelonious Monk and began to make recordings under his own name; each undertaking demonstrated a newfound level of technical discipline, as well as increased harmonic and rhythmic sophistication.

During this period Coltrane developed what came to be known as his “sheets of sound” approach to improvisation, as described by poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka): “The notes that Trane was playing in the solo became more than just one note following another. The notes came so fast, and with so many overtones and undertones, that they had the effect of a piano player striking chords rapidly but somehow articulating separately each note in the chord, and its vibrating subtones.” Or, as Coltrane himself said, “I start in the middle of a sentence and move both directions at once.” The cascade of notes during his powerful solos showed his infatuation with chord progressions, culminating in the virtuoso performance of “Giant Steps” (1959).

Coltrane’s tone on the tenor sax was huge and dark, with clear definition and full body, even in the highest and lowest registers. His vigorous, intense style was original, but traces of his idols Johnny Hodges and Lester Young can be discerned in his legato phrasing and portamento (or, in jazz vernacular, “smearing,” in which the instrument glides from note to note with no discernible breaks). From Monk he learned the technique of multiphonics, by which a reed player can produce multiple tones simultaneously by using a relaxed embouchure (i.e., position of the lips, tongue, and teeth), varied pressure, and special fingerings. In the late 1950s, Coltrane used multiphonics for simple harmony effects (as on his 1959 recording of “Harmonique”); in the 1960s, he employed the technique more frequently, in passionate, screeching musical passages.

Coltrane returned to Davis’s group in 1958, contributing to the “modal phase” albums Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959), both considered essential examples of 1950s modern jazz. (Davis at this point was experimenting with modes—i.e., scale patterns other than major and minor.) His work on these recordings was always proficient and often brilliant, though relatively subdued and cautious.

After ending his association with Davis in 1960, Coltrane formed his own acclaimed quartet, featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones. At this time Coltrane began playing soprano saxophone in addition to tenor. Throughout the early 1960s Coltrane focused on mode-based improvisation in which solos were played atop one- or two-note accompanying figures that were repeated for extended periods of time (typified in his recordings of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things”). At the same time, his study of the musics of India and Africa affected his approach to the soprano sax. These influences, combined with a unique interplay with the drums and the steady vamping of the piano and bass, made the Coltrane quartet one of the most noteworthy jazz groups of the 1960s. Coltrane’s wife, Alice (also a jazz musician and composer), played the piano in his band during the last years of his life.

During the short period between 1965 and his death in 1967, Coltrane’s work expanded into a free, collective (simultaneous) improvisation based on prearranged scales. It was the most radical period of his career, and his avant-garde experiments divided critics and audiences.

Coltrane’s best-known work spanned a period of only 12 years (1955–67), but, because he recorded prolifically, his musical development is well-documented. His somewhat tentative, relatively melodic early style can be heard on the Davis-led albums recorded for the Prestige and Columbia labels during 1955 and ’56. Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane (1957) reveals Coltrane’s growth in terms of technique and harmonic sense, an evolution further chronicled on Davis’s albums Milestones and Kind of Blue. Most of Coltrane’s early solo albums are of a high quality, particularly Blue Train (1957), perhaps the best recorded example of his early hard bop style (see bebop). Recordings from the end of the decade, such as Giant Steps (1959) and My Favorite Things (1960), offer dramatic evidence of his developing virtuosity. Nearly all of the many albums Coltrane recorded during the early 1960s rank as classics; A Love Supreme (1964), a deeply personal album reflecting his religious commitment, is regarded as especially fine work. His final forays into avant-garde and free jazz are represented by Ascension and Meditations (both 1965), as well as several albums released posthumously.

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/john-coltrane-there-was-no-end-to-the-music-john-coltrane-by-rob-armstrong.php

John Coltrane: There Was No End To The Music

All About Jazz

For all their practicing, education and discipline, Coltrane and his fellow jazz contemporaries could count on playing to packed houses every night during the late 1940s and 1950s. Much of the action was on Columbia Avenue, in a world almost entirely eviscerated by Urban Renewal—the building of Yorktown and the expansion of Temple University's campus—and by the race riot of 1964 and its aftereffects of intensifying disinvestment and poverty: the 820 Club at 8th and Columbia, Café Society on Columbia between 12th and 13th Streets, and further west, the Crystal Ball on Columbia between 15th and 16th Streets, the Web Bar on Columbia between 16th and 17th Streets, and The Northwestern and The Point on 23rd and Columbia. Nearby was Café Holiday at 13th and Diamond, the Sun Ray at 16th and Susquehanna and North Philly's largest nightclub in the 1950s, the Blue Note, at 15th Street and Ridge Avenue.

However, the best jazz "institution" of the era was the Woodbine Club, located at 12th and Master Streets, for it was here that jazz musicians would gather at 2AM when their gigs ended. During these sessions, says Pope, musicians learned new ideas and showed younger players techniques that would then be incorporated back into the repertoires and sounds coming out of Philly, all adding to the vibrancy of the institution in this most musical of cities.

Playing consistently, night after night, in clubs allowed Trane and others to develop their unique sound. By the time he left Philadelphia for New York in 1958, "all of the information he had acquired in Philadelphia gave him the opportunity to open up all his ideas and concepts," says Pope. This knowledge was based not just on touring regularly with Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and other major jazz greats, but also in the uniqueness of the tight knit scene developing here and the way Trane would share his ideas with other musicians he knew and trusted in Philadelphia, gathering insight into his own methods in the process.

Miles Davis was a good authority on the saxophonist John Coltrane, who played in one of the trumpeter's bands in the 1950s. Their time spent working together began with Davis's rise to stardom and ended not long after the magnificent Kind of Blue, on which Coltrane played a masterful role. In his autobiography written with Quincy Troupe, Davis summed up Coltrane:

"Trane was the loudest, fastest saxophonist I've ever heard. He could play real fast and real loud at the same time and that's very difficult to do ... it was like he was possessed when he put that horn in his mouth. He was so passionate- fierce – and yet so quiet and gentle when he wasn't playing."

Coltrane, who died of liver failure at 40, has probably been the most influential saxophonist in any musical genre, including Lester Young, Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins and even Charlie Parker. His dazzling solos are now transcribed as exercises for students, while players all over the world still try to mimic his characteristically intense and soulful sound more than 40 years after his death.

Giant Steps, an astonishing tenor-saxophone improvisation Coltrane recorded in 1959, has been a model for aspiring sax players ever since, but it's far more than a technical exercise, pointing the way toward the lava-flows of scales and runs that the critic Ira Gitler famously described as "sheets of sound". Like an engineer obsessively building a machine that could blast free of the restraints of time, space and mortality, Coltrane assembled a distinctive technique from miniscule parts and infinitesimal details. But his mission was to fuse them all into one single, huge, imploring sound in which all the details, while crucial, were no longer individually audible. For him, Giant Steps was more like a first step.

Coltrane forged on through the 60s, shedding and recruiting band-members on the way, providing a model for the difficult art of larger-group free-improv with his 1965 recording Ascension, and in his final years forming an uncompromising new band with his second wife, Alice, on keyboards, saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, and Rashied Ali – a more abstract, textural performer than Elvin Jones had been – on drums and percussion. John Coltrane died in New York on 17 July 1967.

https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/jazz/strickla.htm

As originally published in

The Atlantic Monthly

December 1987

What Coltrane Wanted

The legendary saxophonist forsook lyricism for the quest for ecstasy

by Edward Strickland

JOHN COLTRANE died twenty years ago, on July 17, 1967, at the age of forty. In the years since, his influence has only grown, and the stellar avant-garde saxophonist has become a jazz legend of a stature shared only by Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker. As an instrumentalist Coltrane was technically and imaginatively equal to both; as a composer he was superior, although he has not received the recognition he deserves for this aspect of his work. In composition he excelled in an astonishing number of forms--blues, ballads, spirituals, rhapsodies, elegies, suites, and free-form and cross-cultural works.

The closest contemporary analogy to Coltrane's relentless search for possibilities was the Beatles' redefinition of rock from one album to the next. Yet the distance they traveled from conventional hard rock through sitars and Baroque obligatos to Sergeant Pepper psychedelia and the musical shards of Abbey Road seems short by comparison with Coltrane's journey from hard-bop saxist to daring harmonic and modal improviser to dying prophet speaking in tongues.

Asked by a Swedish disc jockey in 1960 if he was trying to "play what you hear," he said that he was working off set harmonic devices while experimenting with others of which he was not yet certain. Although he was trying to "get the one essential . . . the one single line," he felt forced to play everything, for he was unable to "work what I know down into a more lyrical line" that would be "easily understood." Coltrane never found the one line. Nor was he ever to achieve the "more beautiful . . . more lyrical" sound he aspired to. He complicated rather than simplified his art, making it more visceral, raw, and wild. And even to his greatest fans it was anything but easily understood. In this failure, however, Coltrane contributed far more than he could have in success, for above all, his legacy to his followers is the abiding sense of search, of the musical quest as its own fulfillment.

BORN and raised in North Carolina, Coltrane studied in Philadelphia and after working as a clarinetist in Navy marching and dance bands in 1945-1946 he began a decade of playing with Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Johnny Hodges, and also such undistinguished rhythm-and-blues artists as King Kolax, Bull Moose Jackson, and Daisy Mae and the Hepcats. He came to wide notice in 1955 in the now legendary Miles Davis Quintet and was immediately acknowledged as an original--or an oddity. Critics who in Coltrane's last years all but waved banners to show their devotion to him were among those casting stones for much of his career. At first many urged Davis to fire the weird tenor, but when, in April of 1957, after a year and a half with the quintet, Coltrane left or was dropped (the truth remains unclear), the reason seems to have been indulgence not in stylistic extremism but in heroin and alcohol, problems he conquered that same year. The controversy had to do not only with his harmonic experimentation, on which Dexter Gordon was initially the chief influence, but with the speed (to some, purely chaotic) of his playing and the jaggedness (to some, unmusical) of his phrasing.

All three characteristics were intensified in 1957 during several months with Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot, after which he rejoined Davis, who was now experimenting with sparer chord changes, and became fully involved in what Ira Gitler, in Down Beat, called the "sheets of sound" approach. This technique of runs so rapid as to make the notes virtually indistinguishable seems itself to have been a by-product of Coltrane's harmonic exploration. Coltrane spoke of playing the same chord three or four different ways within a measure or overlapping chords before the change, advancing further the investigation of upper harmonic intervals begun by Charlie Parker and the boppers. Attempting to articulate so many harmonic variants before the change, Coltrane was necessarily led to preternatural velocity and occasionally to asymmetrical subdivision of the beat. Despite Davis's suggestion that Coltrane could trim his twenty-seven or twenty-eight choruses if he tried taking the saxophone out of his mouth, Coltrane's attempt "to explore all the avenues" made him the perfect stylistic complement to Davis, with his cooler style, which featured sustained blue notes and brief cascades of sixteenths almost willfully retreating into silence, and also Monk, with his spare and unpredictable chords and clusters. Davis, characteristically, paid the tersest homage, when, on being told that his music was so complex that it required five saxophonists, he replied that he'd once had Coltrane.

Although in the late fifties Coltrane released a number of sessions for Prestige (and, more notably, Blue Train and Giant Steps for Blue Note and Atlantic respectively) in which he was the nominal bandleader, it was really after leaving Davis for the second time, in 1960, shortly after a European tour, that he came into his own as a creative as well as an interpretive force. His first recording session as leader after the break, on October 21, 1960, produced "My Favorite Things," an astonishing fourteen-minute reinterpretation, or overhaul, of the saccharine show tune, which thrilled jazz fans with its Oriental modalism and Atlantic executives with its unexpected commercial success. In it Coltrane revived the straight soprano sax (whose only previous master in jazz had been Sidney Bechet), and in so doing led a generation of young musicians, from Wayne Shorter to Keith Jarrett to Jon Gibson, to explore the instrument. The work remained Coltrane's signature piece until his death (of liver disease) despite bizarre stylistic metamorphoses in the next five and a half years.

Coltrane signed with Impulse Records in April of 1961 and the next month began rehearsing and playing the long studio sessions for Africa/Brass, a large-band experiment with arrangements by his close friend Eric Dolphy. This was in part an extension of the modal experimentation in which he had been involved with Davis in the late fifties, notably on the landmark Kind of Blue. The modal style replaced chordal progressions as the basis for improvisation, with a slower harmonic rhythm and patterns of intervals corresponding only vaguely to traditional major and minor scales. The modal approach proved to be the modulation from bop to free jazz, as is clear in Coltrane's revolutionary use of a single mode throughout "Africa," the piece that takes up all of side one of the album. Just as his prolonged modal solos were emulated by rock guitarists (the Grateful Dead, the Byrds of "Eight Miles High," the unlamented Iron Butterfly, and others), so the astonishing variety Coltrane superimposed on that single F was, according to the composer Steve Reich, a significant, if ostensibly an unlikely, influence on the development of minimalism. The originator of minimalism, La Monte Young, acknowledges the influence of Coltrane's "My Favorite Things" on his use of rapid permutations and combinations of pitches on sopranino sax to simulate chords as sustained tones.

From the start, and especially from the opening notes of Coltrane's solo, which bursts forth like a tribal summons, "Africa" is the aural equivalent of a journey upriver. The elemental force of this polyrhythmic modalism was unknown in the popular music that came before it. Coltrane experimented with two bassists--a hint of wilder things to come, as he sought progressively to submerge himself in rhythm. He was later to employ congas, bata, various other Latin and African percussion instruments, and, incredibly, two drummers--incredibly insofar as Coltrane already had, in Elvin Jones, the most overpowering drummer in jazz. The addition of Rashied Ali to the drum corps, in November of 1965, made for a short-lived collaboration or, rather, competition between Jones and Ali; a disgruntled Jones left the Coltrane band in March of 1966 to join Duke Ellington's. But it was the culmination of Coltrane's search for the rhythmic equivalent of the oceanic feeling of visionary experience. Having employed the gifted accompanists McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison during the years of the "classic quartet" (late 1961 to mid-1965), Coltrane tended to subordinate them, preferring that his accompanists play spare wide-interval chords and a solid rather than showy bass, which would permit him a maximum of flexibility as a soloist. Coltrane would often take long solos accompanied only by his drummer, and in his penultimate recording session, which produced the posthumous Interstellar Space, he is supported only by Ali. Solo sax against drums (against may be all too accurate a word to describe Coltrane's concert duets with the almost maniacal Jones) was Coltrane's conception of naked music, the lone voice crying not in the wilderness but from some primordial chaos. His music evokes not only the jungle but all that existed before the jungle.

COLTRANE'S spiritual concerns led him to a study of Indian music, some elements of which are present in the album Africa/Brass and more of which are in the cut from the album Impressions titled "India," which was recorded in November of 1961. The same month saw the birth of "Spiritual," featuring exotic and otherworldly solos by Coltrane on soprano sax and Dolphy on bass clarinet. Recorded at the Village Vanguard, the piece made clear, if any doubts remained, that Coltrane was attempting to raise jazz from the saloons to the heavens. No jazzman had attempted so overtly to offer his work as a form of religious expression. If Ornette Coleman was, as some have argued, the seminal stylistic force in sixties avant-garde jazz, Coltrane's Eastern imports were the main influence on the East-West "fusion" in the jazz and rock of the late sixties and afterward. In his use of jazz as prayer and meditation Coltrane was beyond all doubt the principal spiritual force in music.

This is further evident in "Alabama," a riveting elegy for the victims of the infamous Sunday-morning church bombing in Birmingham in 1963. Here, as in the early version of his most famous ballad, "Naima," Coltrane is as spare in phrasing as he is bleak in tone. That tone, criticized by many as hard-edged and emotionally impoverished, is inseparable from Coltrane's achievement, conveying as it does a sense of absolute purity through the abnegation of sentimentality. Sonny Rollins, the contemporary tenor most admired by Coltrane, always had a richer tone, and Coltrane himself said of the mellifluous Stan Getz, "Let's face it--we'd all sound like that if we could." Despite these frequent and generous tributes, Coltrane's aim was different, as is clear in his revival of the soprano sax. Rather than lushness he sought clarity and incisiveness. As with pre-nineteenth-century string players, the rare vibrato was dramatic ornamentation.

Coltrane's religious dedication, which as much as his music made him a role model, especially but by no means exclusively among young blacks, is clearest of all in the album titled A Love Supreme, recorded in late 1964 with Tyner, Jones, and Garrison. The album appeared in early 1965 to great popular and critical acclaim and remains generally acknowledged as Coltrane's masterpiece. In a sense, though, it is stylistically as much a summation as a new direction, for its modalism and incantatory style recall "Spiritual," "India," and the world-weary lyricism of his preceding and still underrated album, Crescent. Within months Coltrane was to shift his emphasis from incantation to the freer-form glossolalia of his last period--a transition evident in a European concert performance of A Love Supreme in mid-1965.

Meditations, recorded a year after A Love Supreme, is the finest creation of the late Coltrane, and possibly of any Coltrane. It may never be as accessible as A Love Supreme, but it is the more revolutionary and compelling work. While some of the creations of Coltrane's last two years are all but amorphous, Meditations succeeds not only for the transcendental force it shares with A Love Supreme but by virtue of the contrasts among the shamanistic frenzy of Coltrane and fellow tenor Pharoah Sanders in the opening movement "The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost" and elsewhere, the sense of stoic resignation and perseverance in the solos of Garrison and Tyner, and the repeated, spiraling phrases of yearning in Coltrane's "Love" and the concluding "Serenity." This unity, encompassing radical stylistic and affective diversity, is the unique feature of Meditations, even in relation to its Ur-version for quartet, which has an additional and quite obtrusive movement. Nothing that came after Meditations approached it in structural complexity and subtlety.

These may be the missing ingredients in the music of Coltrane's final period. The drummer Elvin Jones said, "Only poets can understand it," though maybe only mystics could, for until his final album Coltrane seemingly forsook lyricism for an unfettered quest for ecstasy. The results remain virtually indescribable, and they forestall criticism with the furious directness of their energy. Yet their effect depends more on the abandonment of rationality, which most listeners achieve only intermittently if at all. In fact, it may be the listener himself who is abandoned, for it seems clear that Coltrane is no longer primarily concerned with a human audience. His final recording of "My Favorite Things" and "Naima," at the Village Vanguard in 1966, uses the musical texts as springboards to visionary rhapsody--almost, in fact, as pretexts. All songs become virtually interchangeable, and there is really no point any longer in requests. The only favorite thing he is playing about now is salvation. Coltrane's second wife, Alice, who had by then replaced Tyner as the group's pianist, has remarked, "Some of his latest works aren't musical compositions." This may be their glory and their limitation, the latter progressively more evident in the uninspired emulation by the so-called "Coltrane machines" who followed the last footsteps of the master, and also in the current dismissal of free jazz as a dead end by both jazz mainstreamers and the experimental composer Anthony Davis (who nonetheless recently used Coltrane as a model in the "Mecca" section of his opera X).

The last album that Coltrane recorded was Expression, in February and March of 1967. The album has an aura of twilight, of limbo, particularly in the piece "To Be," in which Coltrane and Sanders play spectral flute and piccolo respectively. The sixteen ametrical minutes of "To Be," which could readily have added to its title the second part of Hamlet's question, are as eerie as any in music.

The most striking characteristic of the album is its sense of consummation, which is clear in the abandonment of developmental structure and often bar divisions, and in the phantasmal rather than propulsive lines that pervade the work. There had always been in Coltrane a profound tension between the pure virtuosity of his elongated phrases and the high sustained cries or eloquent rests that followed. The cries, wails, and shrieks remain in Expression but they are subsumed by the hard-won simplicity that predominates in the album--the lyricism not of "the one essential" line he had sought seven years earlier and never found but one born of courageous resignation. Pater said that all art aspires to the condition of music. Coltrane seems to suggest here that music in turn aspires to the condition of silence.

Those who criticize Coltrane's virtuosic profusion are of the same party as those who found Van Gogh's canvases "too full of paint"--a criticism Henry Miller once compared to the dismissal of a mystic as "too full of God." In Coltrane, sound--often discordant, chaotic, almost unbearable--became the spiritual form of the man, an identification perhaps possible only with a wind instrument, with which the player is of necessity fused more intimately than with strings or percussion. This physical intimacy was all the more intense for his characteristically tight embouchure, the preternatural duration and complexity of his phrases, and his increasing use of overblowing techniques. The whole spectrum of Coltrane's music--the world-weary melancholy and transcendental yearning that ultimately recall Bach more than Parker, the jungle calls and glossolalic shrieks, the whirlwind runs and spare elegies for murdered children and a murderous planet--is at root merely a suffering man's breath. The quality of that music reminds us that the root of the word inspiration is "breathing upon." This country has not produced a greater musician.

Copyright © 1987 by Edward Strickland. All rights reserved. The Atlantic Monthly; December 1987; "What Coltrane Wanted"; Volume 260, No. 6; pages 100-102.

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/coltranes-free-jazz-awesome

November 10, 2014

Coltrane’s Free Jazz Wasn’t Just “A Lot of Noise”

by Richard Brody

The New Yorker

The discovery and release of a previously unknown recording by the saxophonist John Coltrane, who died at the age of forty in 1967, is cause for rejoicing—and I’m rejoicing in “Offering: Live at Temple University,” the release of a tape, made for the school’s radio station, of a concert that Coltrane and his band gave on November 11, 1966, a mere nine months before his death.

I knew and already loved this concert, on the basis of a bootleg of three of its five numbers. But the legitimate release offers much better sound and contains the pièce de résistance: a climactic performance of “My Favorite Things,” the Richard Rodgers tune that Coltrane turned into a jazz classic in 1960. Yet this 1966 performance of it is very different from that of 1960, and, indeed, even from Coltrane recordings from a year or two before the Temple concert. In the intervening years, Coltrane’s musical conception had shifted toward what can conveniently be called “free jazz.”

The term started as the name of an album by one of the form’s key artists, Ornette Coleman, from 1960, even though that recording only hinted at the further extremes of free jazz, some of which were in evidence in Coltrane’s final two years. The idea, roughly, involves playing without a set harmonic structure (the framework of chords that lasts a pre-set number of bars and gives jazz performances a sense of sentences and paragraphs), without a foot-tapping beat, and sometimes even without the notion of solos, allowing musicians to join in or lay out as the spirit moves them. Lacking beat, harmony, and tonality, free jazz cuts the main connection to show tunes, dance-hall performances, or even background music to which jazz owed much of whatever popularity it enjoyed.

There’s a temptation to consider free jazz as a freedom from: freedom from structures and formats and preëxisting patterns of any sort. But it’s also a freedom to: a freedom to musical disinhibition of tone, a vehemence and fervor, as well as a freedom to invent. The very word “freedom” meant something particular to black Americans in the nineteen-sixties. They didn’t have it, and there’s an implicit, and sometimes explicit, political idea in free jazz: a freedom from European styles, a freedom to seek African and other musical heritages, and, also, a freedom to cross-pollinate jazz with other arts. In the process, jazz musicians developed new forms and new moods that reflected a new generation’s experiences and ideals. The politics of free jazz were inseparable from its aesthetic transformation of jazz into overt and self-conscious modernism.

Coltrane’s turn to free jazz, in his last two years of performance, gave rise to a more overtly transcendent yet frenzied yearning. His playing on “Offering” is even more fervent and, at times, furious than it had been, even two years earlier, on the celebrated album “A Love Supreme.” Yet his heightened, trance-like playing has a core of stillness, of devotional tranquility; his music is like a whirlwind with an eye of serenity.

The difference in Coltrane’s own playing goes hand in hand with that of his group over all. In his last years, he radically changed his very conception of his band, and what resulted was a new musical tone. Coltrane’s former group was a classic quartet (featuring the pianist McCoy Tyner, the bassist Jimmy Garrison, and the drummer Elvin Jones). His new band, heard in “Offering,” was a quintet, augmented by the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, in which Coltrane’s wife, Alice Coltrane, replaced Tyner and Rashied Ali replaced Jones. (Garrison stayed in the group, though in the “Offering” concert he was replaced by Sonny Johnson.) Also, for the Temple gig, Coltrane supplemented the band with four more percussionists and two guest alto saxophonists, Coltrane’s longtime acquaintance Arnold Joyner and the teen-ager Steve Knoblauch, whom Coltrane invited to solo on “My Favorite Things.” (The liner notes, by Ashley Kahn, feature their accounts of the concert.) The big group, playing free of harmonic structures and foot-tapping rhythm, gives the succession and shift of musical events a tumultuous, organic flow. In the grand scope of its development and in the tumble of its frenetic incidents, the performances make perfect, natural dramatic sense.

Not everyone seems as enamored of this recording—or, for that matter, of Coltrane’s later performances in general. Geoff Dyer, writing at the New York Review of Books site, describes the music as “shrieking, screaming, and wildness.” He loves Coltrane—the works of the classic quartet, featuring Elvin Jones and McCoy Tyner. But Dyer calls late Coltrane “catastrophic”; and Dyer is an honorable fan. He tells the story of Coltrane’s musical transformations around 1965, and, demeaning the recording of “Offering,” cites approvingly Jones’s view of them:

The epilogue of “But Beautiful” is an essay in which Dyer makes clear that free jazz altogether was already his bête noire—pun entirely intended. He asserts the centrality of “tradition” in jazz—as if it needed his defense—and relies on this principle to justify the limits of his taste. In this essay, too, he writes in veneration of Coltrane’s classic quartet, only to assert that, in Coltrane’s later performances, “there is little beauty but much that is terrible.” Dyer is so bound to his own idea of what jazz is, and to its popular and classical roots, that he can’t hear the ideas of one of its greatest creators. He listens to jazz like a consumer or a patron rather than like an artist; he doesn’t enter into imaginative sympathy with the musicians, and he can’t conceive or, for that matter, feel what the creator of “Spiritual” or “Dearly Beloved” finds necessary in “Interstellar Space” or “Offering.”

In “Offering,” there are astonishing, deeply moving moments in which Coltrane uses his voice—he cries out during a solo by Sanders, and twice sings in a sort of vocalise, pounding his chest to make his voice warble. Dyer writes condescendingly in his review that “these eagerly anticipated moments actually sound a bit daft—which is not to say that they were without value.” They don’t sound “daft” at all; they sound like spontaneous and ingenuous expressions of rapturous joy. But they are gestures that would have had little place amid the prodigious musical strength of Coltrane’s classic quartet. On the other hand, they’re right at home in Coltrane’s open-ended quasi-hangout band, in the familial intimacy that gives rise to its vulnerable furies.

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2008/08/john-coltrane-vs-philosophical.html

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on August 4, 2008):

Monday, August 4, 2008

The Art of John Coltrane vs. The Philosophical Limitations of Jazz Criticism

Book Review

by Kofi Natambu

Coltrane: The story of a sound. By Ben Ratliff.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2007

This is a curiously schizophrenic, self-serving, and ultimately shallow book. On the one hand it proposes to provide readers with a broad general outline of the ‘artistic history’ of John Coltrane’s career and on the other critically examine his ongoing impact and influence, musical and extramusical, on both his contemporaries and subsequent generations of musicians since his early death at the age of forty in 1967.

Throughout, the author--Ben Ratliff, Jazz critic for the New York Times—engages in a highly digressive commentary on what he thinks Coltrane’s career as player, composer, and cultural avatar means to the history of Jazz and to our understanding and appreciation of an individual American aesthetic and cultural icon.

However, these otherwise laudable, useful, and intriguing ambitions are seriously marred by Ratliff’s intellectually reductive presumptions about both the music he proposes to critique and examine and the cultural philosophy of the individual creative personality he wants to portray. The major source of Ratliff’s analytical flaws and blind spots (which are considerable) lies with his studied quasi-philosophical over-reliance and even lazy intellectual dependency on an empirical framework that consistently reduces profound and unsettling questions of aesthetic, cultural and expressive identity and philosophy to almost rudimentary descriptions and examinations of the largely academic categories of style, formal structure, method, and technique(s). Thus we are treated to quite a bit of admittedly lucid but predominately expository writing about how and why Coltrane’s music differs in cosmetic terms from that of other musical styles, traditions, forms, and genres in Western music particularly of the United States and Europe. However, the much broader and more specific historical, social, cultural, ideological, economic, and political contexts of Coltrane’s music (and persona) as it was actually created, produced, marketed, distributed and consumed in the society he and his music lived/lives in is either ignored or given very short shrift in Ratliff’s analysis.

Ratliff’s annoying and often condescending tendency to churlishly dismiss or discount the significance of the central historical roles that political economy, racism, and most importantly, competing cultural and aesthetic philosophies have played and continue to play in both the creative and social ecosphere of Jazz is a major weakness in a book that almost coyly demands that we accept, if not embrace, its highly problematic fundamental premises. These premises are the following: That Coltrane was not primarily interested in expressing and supporting creatively provocative ideas and values per se but in obsessively pursuing matters of craft, stylistic expression, and technical prowess; that Coltrane was not really interested in the social, cultural, and political implications of what he was playing or the form and content of the highly varied reactions of audiences to what he was playing and why; that the 1960s ‘black power’ movement had a negative or distorting effect on the study, appreciation, and understanding of what the complex musical evolution known as “late Coltrane” (1965-1967) meant to the artist and black and white American audiences alike. And that to fully grasp what Coltrane finally accomplished or was trying to do in his work one had to surrender to a romantic aesthetic notion rooted in the 19th century and later promulgated in the 20th century by the late modernist poet Robert Lowell (an aesthetic theory Ratliff suggestively paraphrases and appropriates for a historically different artistic and cultural context) that Coltrane and his music represented and embodied the “monotony of the sublime” found in other radical forms of American art making. Further Ratliff asserts that Coltrane was making a music of “his interior cosmos” and was finally consumed by a music of “meditation and chant” in the last years after December 1964 (and the pivotal appearance of Coltrane’s magnum opus composition suite ‘A Love Supreme’) until his death in July, 1967.

What Ratliff also fails to address and seriously investigate is the complex and varied receptions of, and responses to, this music by other musicians and the larger listening audience meant in terms of the history of Jazz up until the late 1960s (and by implication ever afterward). While Ratliff readily acknowledges and broadly surveys the intense chaotic volatility of art, society, and culture of that era (and Coltrane’s important, even mythic, participation in it) what he fails to provide is an informed analytical and theoretical critique of precisely why Coltrane, Jazz in general, and the larger society remained in a dire and fundamental conflict over what role the concept of “art” and its various uses and identities should or could be in the music. At one point Ratliff even mentions that as far as he knew Coltrane had never publicly used or uttered the word ‘art’ to describe what his music was about. I was hoping that Ratliff would subsequently examine what he thought this fact meant to his general analysis of Jazz as a musical aesthetic in the post-WWII period, but he simply chalked it up to Coltrane’s tendency toward verbal reticence in publicly talking about his music in openly intellectual terms and his personal indifference to categorical labeling. The result is a book that manages to raise important and previously neglected questions about the specific nature and identity of Coltrane’s work and his profound contributions to American music, while at the same time almost willfully refusing to take any discernible theoretical or ideological position(s) on what Ratliff himself as critic and historian thought Coltrane’s music and reputation represents.

It is Ratliff’s failure to seriously confront and intellectually engage the previously published critical literature on both Coltrane and Jazz of the 1955-1970 era that is most disapointing. Among this rather extensive body of texts is very important work by a number of African American intellectuals, historians, and critics like Dr. C.O. Simpkins (who wrote a major book on Coltrane as early as 1975—which Ratliff himself even curiously acknowledges as “one of the best Coltrane biographies” and then proceeds to say not one more word about), the late James Stewart who wrote a number of powerful and influential essays on Jazz of the 1960s and ‘70s, Bill Cole, prominent ethnomusicologist and former Professor of Music at Dartmouth College who wrote a seminal musical biography on Coltrane in 1976, the extraordinary poet and cultural historian A.B. Spellman, author of one of the most prescient books ever published on black avant-garde music ‘Four Lives in the BeBop Business’ (later titled ‘Black Music: Four Lives) in 1966, and finally one of the leading Jazz critics and historians in the entire modern canon of 20th century Jazz literature, the legendary poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, and activist Amiri Baraka (formerly Leroi Jones). It is especially revealing that when Ratliff does briefly mention Baraka’s work (he quotes part of a poem by him on Coltrane and also a small segment from an essay on Black nationalism in his art) he doesn’t really focus on Baraka as a music critic; rather he summarizes in a couple sentences what Baraka’s fundamental stance was in the late 1960s on the cultural and social uses and function of what black art is or could be. But tellingly Ratliff does not talk about or examine Baraka’s major Jazz criticism of this period (1964-1967) qua criticism. This omission is not merely incidental but goes to the heart of what Ratliff refuses to deal with generally in his text: the larger meaning of the contentious discourse raging then and now over what Coltrane and the so-called ‘Free-Jazz’ players and composers of the 1960s and ‘70s represented (and currently represents) to an understanding of the Jazz tradition and U.S. culture generally over the past century.

This is especially significant with respect to the philosophical acuity and depth of the major book of Jazz criticism that Baraka published in 1967 entitled ‘Black Music.’ Dedicated to ‘John Coltrane, the heaviest spirit’ this book, made up of formerly published magazine essays and articles comprises one of the most important statements ever conceived and written about the specific dynamics, formal and stylistic challenges, cultural theory, and ideological identity of the so-called black musical “avant garde” of the 1959-1967 era. Pivotal to this text’s visionary stance is the first essay from the book, which is quoted at the beginning of this review. “Jazz and the White Critic” published in 1963 and which initially appeared in Down Beat magazine, was a major advance in the history of Jazz criticism because it openly and courageously addressed one of the most important but largely ignored issues in the canonical history of Jazz writing—the contradiction and separation between the major black players of the music and the almost completely exclusive white writers and critics of the music. By raising questions about what this contradiction said and implied about Jazz music and its history as art, science, history, sociology, ideology, and political economy, Baraka revealed that what white critics said about the music, reflected intellectual, cultural, and personal biases that had to be acknowledged and taken serious account of.

Ironically, Ratliff as critic and historian ultimately avoids these and other related issues by insisting that the individual icon in Jazz (like Coltrane) is not only an indispensable touchstone in the music’s evolution but that even more importantly the bands that they and others lead are even more significant. As Ratliff puts it at the end of his study “The truth of Jazz is in its bands.” While this statement seems accurate enough on its surface with its philosophical emphasis on the time honored Western notion of the “artist” as being central to an understanding and appreciation of any cultural or aesthetic expression, it appears that Ratliff winds up failing to notice that Jazz is first and foremost a public, collective, collaborative, and thus social expression whose major focus is not merely on the players and composers involved but on the communities that it engages in any given cultural environment. Thus the role of the individual “genius” in the music’s identity and evolution is not the dominant one. Of course, the marketing and processed packaging of the individual musician (or ensemble) as readily available commodity in the economic context of the capitalist marketplace where commodities are routinely promoted, bought, and sold may give the distinct impression that the individual “great man or woman” is the most important driving force behind the music but that would be an ultimately false and greatly mistaken notion. Even with such astonishingly advanced and gifted players and composers as the late, great John Coltrane it would be far more accurate to suggest that actually “the truth of Jazz lies in its music.” As critic and historian Ratliff misses, neglects, or ignores this crucial point and his book (and his analysis of Coltrane) greatly suffers for it.

http://www.jerryjazzmusician.com/2014/01/liner-notes-live-birdland-leroi-jones/

Liner Notes: LeRoi Jones on John Coltrane’s Live at Birdland

January 31, 2014

Political, fiery, critical, poetic, inspirational…All of this shows up in Amiri Baraka’s brilliant liner notes to the 1963 recording of John Coltrane’s Live at Birdland. At the time known as LeRoi Jones, Baraka’s liner notes to this album were the first time the jazz writer Stanley Crouch “had seen that kind of poetic sensibility brought to the discussion of jazz. It was as new to me as the way Coltrane and his band were reinventing the 4/4 swing, blues, ballads, and Afro-Hispanic rhythms that are the four elements essential to jazz…His was the first Negro voice that sailed to the center of my taste by combining the spunk and the raw horrors of the sidewalk with the library, for an elegant manhandling of the form.”

These notes were written at the time of Jones’ 1963 Down Beat essay “Jazz and the White Critic,” which, in the words of Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and its Critics author John Gennari, was a “challenge to jazz writers of all backgrounds to reckon with the lived experience of black Americans and to consider how this experience had been embedded in the notes, tones, and rhythms of the music.” Keep that in mind when reading these notes…

One of the most baffling things about America is that despite its essentially vile profile, so much beauty continues to exist here. Perhaps it’s as so many thinkers have said, that it is because of the vileness, or call it adversity, that such beauty does exist. (As balance?).

Thinking along these lines, even the title of this album can be rendered “symbolic” and more directly meaningful. John Coltrane Live At Birdland. To me, Birdland is only America in microcosm, and we know how high the mortality rate is for artists in this instant tomb. Yet, the title tells us that John Coltrane is there live. In this tiny America where the most delirious happiness can only be caused by the dollar, a man continues to make daring reference to some other kind of thought. Impossible? Listen to I Want To Talk About You.

Coltrane apparently doesn’t need an ivory tower. Now that he is a master, and the slightest sound from his instrument is valuable, he is able, literally, to make his statements anywhere. Birdland included. It does not seem to matter to him (nor should it) that hovering in the background are people and artifacts that have no more to do with his music than silence.

But now I forget why I went off into this direction. Nightclubs are, finally, nightclubs. And their value is that even though they are raised or opened strictly for gain (and not the musician’s) if we go to them and are able to sit, as I was for this session, and hold on, if it is a master we are listening to, we are very likely to be moved beyond the pettiness and stupidity of our beautiful enemies. John Coltrane can do this for us. He has done it for me many times, and his music is one of the reasons suicide seems so boring.

There are three numbers on the album that were recorded Live at Birdland, Afro-Blue, I Want To Talk About You, and The Promise. And while some of the non-musical hysteria has vanished from the recording, that is, after riding a subway through New York’s bowels, and that subway full of all the things any man should expect to find in some thing’s bowels, and then coming up stairs, to the street, and walking slowly, head down, through the traffic and failure that does shape the area, and then entering “The Jazz Corner Of The World” (a temple erected in praise of what God?), and then finally amidst that noise and glare to hear a man destroy all of it, completely, like Sodom, with just the first few notes from his horn, your “critical” sense can be erased completely, and that experience can place you somewhere a long way off from anything ugly. Still, what was of musical value that I heard that night does remain, and the emotions … some of them completely new … that I experience at each “objective” rehearing of this music are as valuable as anything else I know about. And all of this is on this record, and the studio pieces, Alabama and Your Lady, are among the strongest efforts on the album.

But since records, recorded “Live” or otherwise, are artifacts, that is the way they should be talked about. The few people who were at Birdland the night of October 8 who really beard what Coltrane, Jones, Tyner and Garrison were doing will probably tell you, if you ever run into them, just “exactly” what went on, and how we all reacted. I wish I had a list of all those people so that interested parties could call them and get the whole story, but then, almost anyone who’s heard John and the others at a nightclub or some kind of live performance has got stories of their own. I know I’ve got a lot of them.

But in terms of the artifact, what you’re holding in your hand now, I would say first of all, if you can hear, you’re going to be moved. Afro-Blue, the long tune of the album, is in the tradition of all the African-Indian-Latin flavored pieces Trane has done on soprano, since picking up that horn and reclaiming it as a jazz instrument. (In this sense The Promise is in that same genre.) Even though the head-melody is simple and song-like, it is a song given by making what feels to me like an almost unintelligible lyricism suddenly marvelously intelligible. McCoy Tyner too, who is the polished formalist of the group, makes his less cautious lyrical statements on this, but driven, almost harassed, as Trane is too, by the mad ritual drama that Elvin Jones taunts them with. There is no way to “describe” Elvin’s playing, or, I would suppose, Elvin himself. The long tag of Afro-Blue, with Elvin thrashing and cursing beneath Trane’s line, is unbelievable. Beautiful has nothing to do with it, but it is. (I got up and danced while writing these notes, screaming at Elvin to cool it.) You feel when this is finished, amidst the crashing cymbals, bombarded tomtoms, and above it all Coltrane’s soprano singing like any song you can remember, that it really did not have to end at all, that this music could have gone on and on like the wild pulse of all living.

Trane did Billy Eckstine’s I Want To Talk About You some years ago, but I don’t think it’s any news that his style has changed a great deal since then, and so this Talk is something completely different. It is now a virtuoso tenor piece (and the tenor is still Trane’s “real” instrument) and instead of the simplistic though touching note-for-note replay of the ballad’s line, on this performance each note is tested given a slight tremolo or emotional vibrato (note to chord to scale reference), which makes it seem as if each one of the notes is given the possibility of “infinite” qualification, i.e., scalar or chordal, expansion, “threatening” us with those “sheets of sound,” but also proving that the ballad as it was written was only the beginning of the story. The tag on this is an unaccompanied solo of Trane’s that is a tenor lesson-performance that seems to get more precisely stated with each rehearing.

If you have heard Slow Dance or After The Rain, then you might be prepared for the kind of feeling that Alabama carries. I didn’t realize until now what a beautiful word Alabama is. That is one function of art, to reveal beauty, common or uncommon, uncommonly. And that’s what Trane does. Bob Thiele asked Trane if the title “had any significance to today’s problems.” I suppose he meant literally. Coltrane answered, “It represents, musically, something that I saw down there translated into music from inside me.” Which is to say, Listen. And what we’re given is a slow delicate introspective sadness, almost hopelessness, except for Elvin, rising in the background like something out of nature … a fattening thunder, storm clouds or jungle war clouds. The whole is a frightening emotional portrait of some place, in these musicians’ feelings. If that “real” Alabama was the catalyst, more power to it, and may it be this beautiful, even in its destruction.

Your Lady is the sweetest song in the album. And it is pure song, say, as an accompaniment for some very elegant uptown song and dance man. Elvin Jones’ heavy tingling parallel counterpoint sweeps the line along, and the way he is able to solo constantly beneath Trane’s flights, commenting, extending, or just going off on his own, is a very important part of the total sound and effect of this Coltrane group. Jimmy Garrison’s constancy and power, which must be fantastic to support, stimulate and push this group of powerful (and diverse) personalities, is already almost legendary. On tunes like Lady or Afro-Blue Garrison’s bass booms so symmetrically and steadily and emotionally, and again, with such strength, that one wild guess that he must be able to tear safes open with his fingers. All the music on this album is Live, whether it was recorded above drinking and talk at Birdland, in the studio. There is a daringly human quality to John Coltrane’s music that makes itself felt, wherever he records. If you can hear, this music will make you think of a lot of weird and wonderful things. You might even become one of them.

http://decanting-cerebral.tumblr.com/post/72872532210/amiri-baraka-speaks-of-john-coltrane

10th Jan 2014 | 7 notes

Amiri Baraka Speaks Of John Coltrane

1. Trane emerged as the process of historical clarification itself, of a particular social/aesthetic development. When we see him standing next to Bird and Diz, an excited young inlooker inside the torrent of the rising bop statement, right next to the chief creators of that fervent expression of new black life, we are seeing actually point and line, note and phrase of the continuum. As if we could also see Louis and Bechet hovering over them, with Pres hovering just to the side awaiting his entrance, and then beyond, in a deeper, yet-to-be-revealed hover, Pharoah and Albert and David and Wynton or Olu in the mist, there about to be, when called by the notes of what had struck yet before all mentioned.

2. Trane carried the deepness in as thru Bird and Diz, and back to us. He reclaimed the bop fire, the Africa, polyrythmic, improvisational, blue, spirituality of us. The starter of one thing yet the anchor of something before. In the relay of our constant rise and rerise, phoenix describing its birth as a description of yet another (though there is not another) process. Trane carrying Bird-Diz bop revolution and its opposing force to the death force of slavery and corporate co-optation, went through various changes in life, in music. He carried the Southern black church music, and blues and rhythm & blues, as way stations of his personal development, not just theory or abstract history. He played in all these musics and was all these persons. His apprenticeship was extensive and deep; the changes a revealed continuity.

3. The point of demarcation was Miles’ classic quintet, with Cannonball the other up-front stylistic vector. Style and philosophy confirmed each other. As I have said before, Cannonball was Miles’ confection of blues that would later be called fusion. Simple and charming in that context, but very soon commercial on the way to not. Trane, on the other side, was the way of expressionism. Nuclear and carrying the rush of birth and death and rebirth and redeath and new life and yet again forever, what is, as the Africans said, Is Is. Ja Is (Jazz) The Come Music.

4. The ‘60s, when he appeared full-up, was a period, a rhythm of intensity, the giant steps of revolution. This is why we always associate him with Malcom X, as a parallel of that turbulence. Trane’s annihilation of the popular song, so-called, was its restatement as a broader, more universal popular. His “My Favorite Things” could not be Hollywood’s. Hollywood is to make animalism and exploitation glamorous, and Trane was trying to speak of what will exist beyond animals, what had created them, and what will carry them away as waste. What is disposed.

5. Trane’s constant assaults on the given, the status quo, the Tin Pan Alley of the soul, was what Malcolm attempted in our social life. And both African Americans, they carried that reference, Black Life, as their starting point and historical confirmation. The Truth sounds bland only if we don’t understand what it is said in opposition to. Since it is transcendent, invincible, existent even past whatever else we claim exists. Even the lie must use real life as a reference to trick us, as it claims to be truth. But Trane made no claims, either in his life or his work - what he did, he got from life, and we either recognize it with our selves or risk being wasted. Like Malcolm, what he was was reality; not to grasp it defines the quality of our consciousness, our closeness to what cannot finally be denied.

–- Amiri Baraka, “The Coltrane Legacy,” from liner notes included with “The Last Giant: The John Coltrane Anthology,” Rhino Records, 1993

http://edwardbyrne.blogspot.com/2008/09/john-coltrane-michael-s-harper-and.html

Monday, September 22, 2008

John Coltrane, Michael S. Harper, and Amiri Baraka: Jazz Music and Poetry

In Jazz Is, his collection of reflections on jazz musicians, Nat Hentoff describes John Coltrane: “Coltrane, a man of almost unbelievable gentleness made human to us lesser mortals by his very occasional rages. Coltrane, an authentically spiritual man, but not innocent of carnal imperatives. Or perhaps more accurately, a man, in his last years, especially but not exclusively consumed by affairs of the spirit. That is, having constructed a personal world view (or view of the cosmos) on a residue of Christianity and an infusion of Eastern meditative practices and concerns, Coltrane became a theosophist of jazz. The music was a way of self-purgation so that he could learn more about himself to the end of making himself and his music part of the unity of all being. He truly believed this, and in this respect, as well as musically, he has been a powerful influence on many musicians since.”

As we approach John Coltrane’s birthday tomorrow (born September 23, 1926), this occasion offers another opportunity to recognize the close associations between jazz and poetry during the last half-century. Perhaps no example displays the merging of these two art forms better than Michael S, Harper’s “Dear John, Dear Coltrane,” the title poem from his 1970 collection that responds to Coltrane’s music, particularly his magnificent 1965 recording, A Love Supreme. (A rare film clip of Coltrane performing an excerpt of “A Love Supreme” appears above.) Harper explains his poem actually was written just before Coltrane’s death in 1967, yet the poem’s later publication and its content certainly lend a sense of elegy to the work.

DEAR JOHN, DEAR COLTRANE

by Michael S. Harper

a love supreme, a love supreme

a love supreme, a love supreme

Sex fingers toes

in the marketplace

near your father's church

in Hamlet, North Carolina—

witness to this love

in this calm fallow

of these minds,

there is no substitute for pain:

genitals gone or going,

seed burned out,

you tuck the roots in the earth,

turn back, and move

by river through the swamps,

singing: a love supreme, a love supreme;

what does it all mean?

Loss, so great each black

woman expects your failure

in mute change, the seed gone.

You plod up into the electric city—

your song now crystal and

the blues. You pick up the horn

with some will and blow

into the freezing night:

a love supreme, a love supreme—

Dawn comes and you cook

up the thick sin 'tween

impotence and death, fuel

the tenor sax cannibal

heart, genitals, and sweat

that makes you clean—

a love supreme, a love supreme—

Why you so black?

cause I am

why you so funky?

cause I am

why you so black?

cause I am

why you so sweet?

cause I am

why you so black?

cause I am

a love supreme, a love supreme:

So sick

you couldn't play Naima,

so flat we ached

for song you'd concealed

with your own blood,

your diseased liver gave

out its purity,

the inflated heart

pumps out, the tenor kiss,

tenor love:

a love supreme, a love supreme—

a love supreme, a love supreme—

Some of Harper’s own comments on John Coltrane, jazz, spirituality, and this poem inspired by Coltrane’s music or biographical details are engaging and enlightening:

Black musicians have always melded the private and the historical into the aesthetics of human speech and music, the blues and jazz. The blues and jazz are the finest extensions of a bedrock of the testamental process. Blacks have been witnesses victims; they have paid their dues. “Dear John, Dear Coltrane” was written before John Coltrane died; its aim is the redemptive nature of black experience in terms of the private life of a black musician. Coltrane’s music should be seen as a progression from the personal to incantation and prophesy. It is a fusing of tenderness, pain, and power in their melding, and the [furbishing] is at once an internal and external journey or passage: to live with integrity means “to live”—“to create”; its anthem—“there is no substitute for pain”—The poem is a declaration of tenderness, and a reminder to the reader of a suffering beyond the personal and historical to the cultural, that there can be no reservations fixed to sensibility, that personality gives power through the synthesis of personal history and the overtones of America in and by contact. The poem begins with a catalog of sexual trophies, for whites, a lesson to blacks not to assert their manhood, and that black men are suspect because they are potent. The mingling of trophy and Christian vision, Coltrane’s minister-father, indicates an emphasis on physical facts—that there is no refinement beyond the body. The antiphonal, call-response/retort stanza simulates the black church, and gives the answer of renewal to any question raised—“cause I am.” It is Coltrane himself who chants, in life, “a love supreme”; jazz and the blues, as open-ended forms, cannot be programmatic or abstract, but modal . . .. Coltrane’s music is the recognition and embodiment of life-force; his music is testament in modal forms of expression that unfold in their many modal aspects. His music testifies to life; one is witness to the spirit and power of life; and one is rejuvenated and renewed in a living experience, the music that provides images strong enough to give back that power that renews. . ..

Len Lyons, in The 101 Best Jazz Albums: A History of Jazz on Records, has written about Coltrane’s music: “A Love Supreme, recorded in December, is a remarkably warm, hopeful, and energetic outpouring. Coltrane was explicit about the religious inspiration of the music in his poem which serves as the album’s liner notes. John once told his mother that he had experienced visions of God while preparing the music, which was ominous to her because she felt that ‘when someone is seeing God, that means he is going to die.’”

Although obviously not demonstrating the quality of Harper’s poetry, John Coltrane explicitly indicated his own understanding of the interaction between poetry and music with the inclusion of his poem as guidance to listeners in the liner notes for A Love Supreme:

A LOVE SUPREME

by John Coltrane

I will do all I can to be worthy of Thee O Lord.

It all has to do with it.

Thank you God.

Peace.

There is none other.

God is. It is so beautiful. Thank you God. God is all.

Help us to resolve our fears and weaknesses.

Thank you God.

In You all things are possible.

We know. God made us so.

Keep your eye on God.

God is. he always was. he always will be.

No Matter what . . . it is God.

He is gracious and merciful.

It is most important that I know Thee.

Words, sounds, speech, men, memory, thoughts,

fears and emotions—time—all related . . .

all made from one . . . all made in one.

Blessed be His name.

Thought waves—heat waves—all vibrations—

all paths lead to God. Thank you God.

His way . . . it is so lovely . . . it is gracious.

it is merciful — Thank you God.

One thought can produce millions of vibrations

and they all go back to God . . . everything does.

Thank you God.

Have no fear . . . believe . . . Thank you God.

The universe has many wonders. God is all.

His way . . . it is so wonderful.

Thoughts—deeds—vibrations, etc.

They all go back to God and He cleanses all.

He is gracious and merciful . . .

Thank you God.

Glory to God . . . God is so alive.

God is.

God loves.

May I be acceptable in thy sight.

We are all one in His grace.

The fact that we do exist is acknowledgement

of Thee O Lord.

Thank you God.

God will wash away all our tears . . .

He always has . . .

He always will.

Seek Him everyday. In all ways seek God everyday.

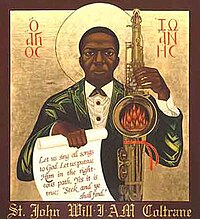

Let us sing all songs to God

To whom all praise is due . . . praise God.

No road is an easy one, but they all go back to God.

With all we share God.

It is all with god.

It is all with Thee.

Obey the Lord

Blessed is He.

We are all from one thing . . . the will of God . . .

thank you God

I have seen God—I have seen ungodly—

none can be greater—none can compare to God.

Thank you God.

He will remake us . . . He always has and he

always will.

It is true—blessed be His name—thank you God.

God breathes through us so completely . . .

so gently we hardly feel it . . . yet,

it is everything.

Thank you God.

ELATIONS—ELEGANCE—EXALTATION—

All from God.

Thank you God. Amen.

In the liner notes to the Coltrane retrospective album released by Rhino Records in 1993, The Last Giant: The John Coltrane Anthology, poet Amiri Baraka reported on the inspiration for his poem dedicated to Coltrane and imitative of Coltrane’s music: “The poem ‘I Love Music’ was written to recall when I was locked up in solitary confinement after the Newark rebellions in 1967. I sat one afternoon and whistled all the Trane I remembered. And then later that afternoon they told me he had died. But I knew even then that that was impossible.” (A recording of Amiri Baraka performing “I Love Music” is available as an mp3 at the University of Pennsylvania archives.) As Baraka suggested then, and now as we remember this significant musician on his birthday, John Coltrane’s spirit remains alive in his recordings, as well as in the music and the poetry later composed by the many he influenced or inspired.

http://www.njarts.net/350-jersey-songs/i-love-music-for-john-coltrane-amiri-baraka/

‘I Love Music (For John Coltrane),’ Amiri Baraka

by Jay Lustig | March 16, 2015

New Jersey Arts

New Jersey poet and activist Amiri Baraka was inspired by music, wrote about music, and collaborated with musicians throughout his entire career. The Newark native — who died last year at the age of 79, and was the father of current Newark mayor Ras Baraka — audaciously tried to summon the wild, liberating spirit of John Coltrane with his words in the 1982 live version of “I Love Music (For John Coltrane)” that can be heard in the YouTube video below. He is backed on the recording by the free jazz group Air (saxophonist Henry Threadgill, bassist Fred Hopkins and drummer Steve McCall).

“The poem ‘I Love Music’ was written to recall when I was locked up in solitary confinement after the Newark rebellions in 1967,” Baraka once said.”I sat one afternoon and whistled all the Trane I remembered. And then later that afternoon they told me he had died. But I knew even then that that was impossible.”

Coltrane did in fact die on July 17, 1967, the last day of the Newark riots. What Baraka meant, I’m sure, was that the spirit of his music would never die.

New Jersey celebrated its 350th birthday last year. And in the 350 Jersey Songs series, we are marking the occasion by posting 350 songs — one a day, for almost a year — that have something to do with the state, its musical history, or both. We started in September 2014, and will keep going until late in the summer.

http://www.npr.org/2000/10/23/148148986/a-love-supreme

The Story Of 'A Love Supreme'

March 07, 2012

by Eric Westervelt

Listen To The Story

All Things Considered

National Public Radiio (NPR)

AUDIO: 12:56: <iframe src="http://www.npr.org/player/embed/148148986/147872677" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no"></iframe>

John Coltrane recorded A Love Supreme

in December of 1964 and released it the following year. He presented it

as a spiritual declaration that his musical devotion was now

intertwined with his faith in God. In many ways, the album mirrors

Coltrane's spiritual quest that grew out of his personal troubles,

including a long struggle with drug and alcohol addiction.

John Coltrane recorded A Love Supreme

in December of 1964 and released it the following year. He presented it

as a spiritual declaration that his musical devotion was now

intertwined with his faith in God. In many ways, the album mirrors

Coltrane's spiritual quest that grew out of his personal troubles,

including a long struggle with drug and alcohol addiction.